While my primary historical fascination is the 11th and 12th century in the British Isles, I do find the clothing and adornments of other periods and locations pretty and thought about creating a few of them for myself. And one of those times is during the reign of Henry VIII. Two items in particular have caught my interest – the French Hood and outer gown’s split skirt with the contrasting material showing.

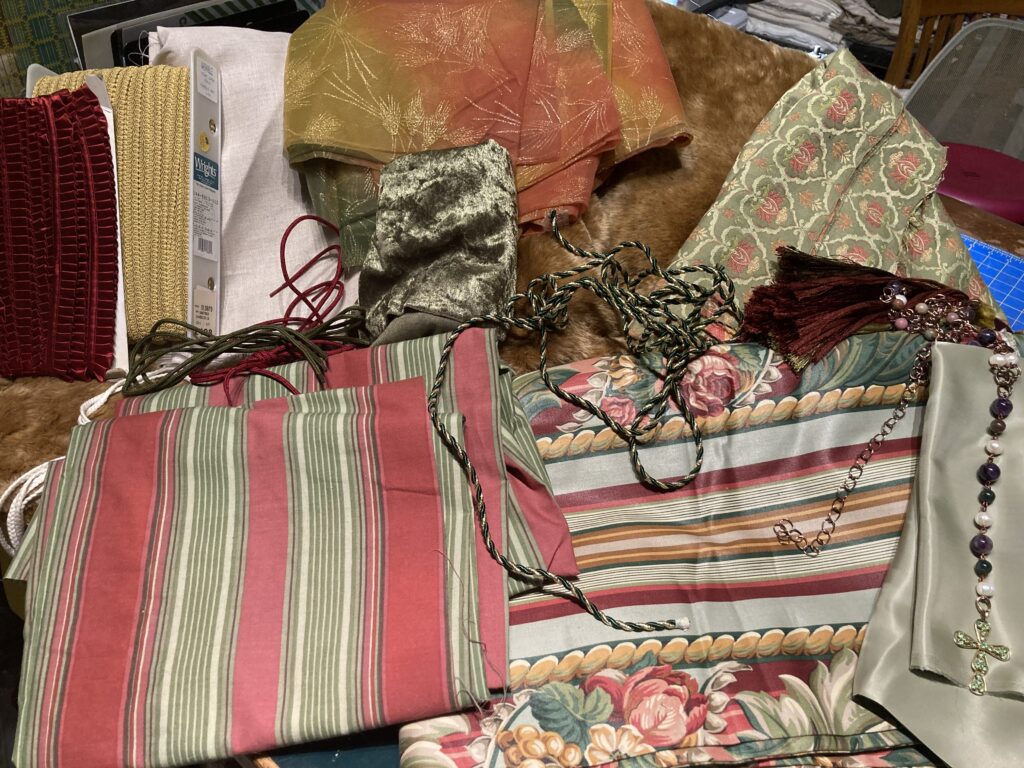

About five years ago I came across a small collection of fabrics that made me once again really consider making an early Tudor outfit for myself. I was attending a quilt show with a few friends, most quilt guilds have a boutique area set up where members can donate material for the guild to sell. And as I know from working several shows – it is not uncommon to receive very un-quilt-like fabric as well. Which occurred in this case – within a side area was a lot of material more suited to clothing or home décor where I found the two striped fabrics and the pale green brocade with the floral designs. All under a sign saying “FREE” – admittedly one of my favorite words!

I had heard of the garb challenge the Barony Beyond the Mountain ran and thought it was a fascinating idea. I just had little belief that I could make something more intricate than an Apron Dress in the typical time frame. But with the pandemic restrictions and adjusting the time frame to create the outfit extended – I thought “I guess I could give it a shot”. So, I began looking at extant images, re-enacting groups and videos, and the fabrics I had been holding onto as well as some additional textiles I had acquired in the last few years.

One of the parameters I had to take into consideration was my personal temperature regulation. For the last seven years I have had the challenge of trying to not overheat, even in winter, especially when wearing most forms of garb. This meant that I wanted to stay away from any form of corset or “bodies”, I was leaning away from using any form of fur (real or artificial), and had to consider the best outfit to let some air circulate. In this instance – the use of a farthingale would keep the majority of the gowns’ weight off my legs and let some air movement happen underneath

Another of my personal parameters involved just how Historically Accurate (HA) I felt the outfit needed to be. While I can see the benefits of recreating a specific outfit or using only HA materials and techniques, that did not really resonate with me. I am more likely to create outfits that reflect my personal sense of style and colors, thereby following the C portion of the SCA – Creative.

While I was locked in with my choice of collected materials, I did have access to more breathable fabrics I could use for both the shift and farthingale – linen. I also found not only some silk for which I cannot remember its origin, and an unhealthy collection of trims. So off I went into looking at various styles, designs, components and variations.

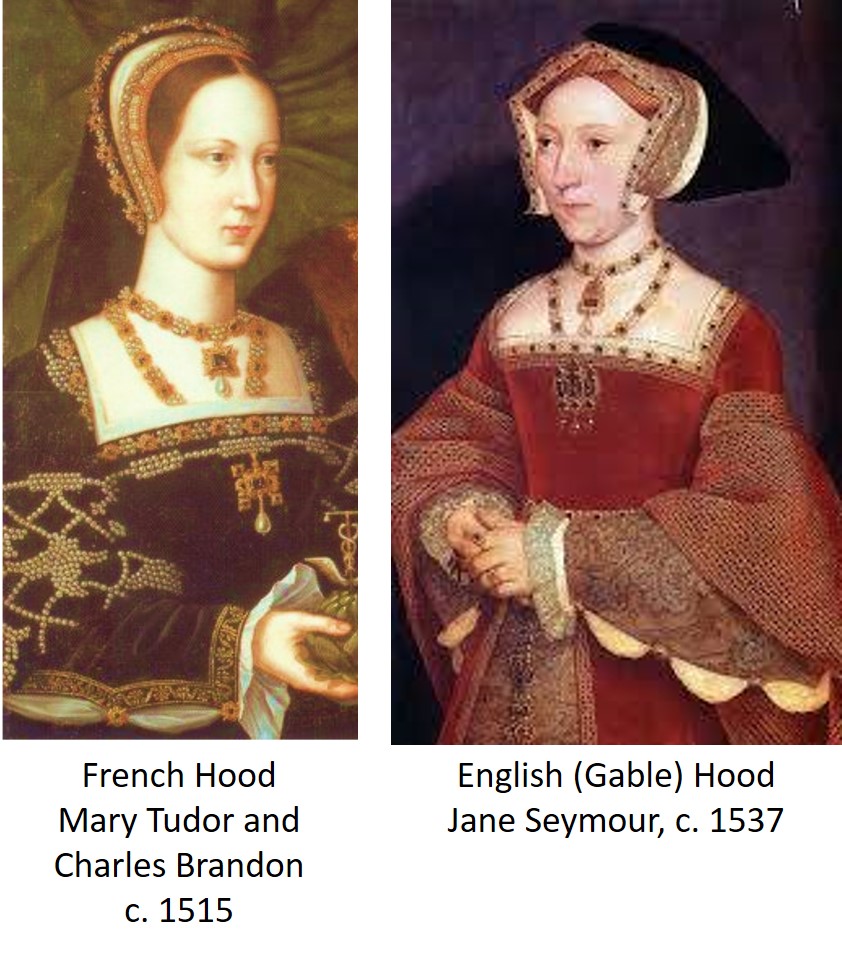

After looking at dozens of dress options I found myself going back frequently to a portrait of Jane Seymour 1. The two features of this outfit that spoke to me were the neckline ornament, or billiments, was attached to the under gown, or kirtle. This allowed the outer gown to be laced up the front with the lacings covered with a stomacher. Which is what this portrait shows as you can just see the pins along the edge of the stomacher holding it in place. This would explain why the ornamentation was not applied to the outer gown, And, this was also mentioned as part of a presentation at Hampton Court by costumed interpreters based on their research 2.

I also was drawn to not needing to be laced into a corset, which did not really become a standard item until a few years later 3. I stiffened the bodice of the kirtle and gown with an inner layer of stiff Duck Cloth and heavy interfacing. This not only provides bust support but reinforces the lacing holes, allowing them to be set very tight, another part of the bust support, and it improves the posture!

I did not have any of the requisite under garments for this period as this was my first go at Tudor style. I acquired two commercial patterns to give me the basic construction steps and fabric requirements 4,5. After some internet research and pricing I ordered the steel boning needed for the farthingale along with twill tape and some lining fabric, items as a quilter I did not have readily at hand.

One thing I found is that there is a wide variety of opinion as to just what the “proper” ratio should be for a farthingale. So, my first iteration I felt was much too wide – more like an 1860s crinoline. So, I took apart the two lower hoops and reduced them.

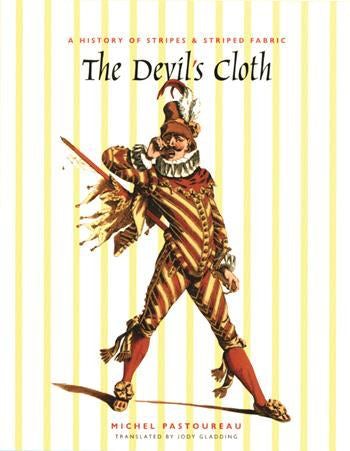

When I began to consider my documentation, I became aware that there seemed to be no examples of striped fabrics in Tudor England, but I did see Spanish and Italian gowns with stripes. That is when I came to read portions of a book by Michel Pastoureau6. One of the things he mentions, and then provides documentation for, is that “…preserved since XII-XIII century, abundant documentation shows that striped clothing was considered shameful, degrading and downright diabolical. Striped attire was worn by executioners and prostitutes. In medieval Europe striped suits were worn by all sorts of outcasts — circus performers, jesters, lepers, cripples, heretics and illegitimate children.”

These are views that carry through the 20th century as seen in the large number of prisons that clothed the inhabitants in striped outfits. However, I again am looking at being Creative in my endeavors and am comfortable using the stripes.

As mentioned earlier I have had issues with body temperature regulation and many of the gowns I saw examples of lined the gown’s sleeves with fur. I elected to use a lighter material and make “fur” sleeve linings that can be attached or removed based on the weather, since we currently are not experiencing the downturn in temperatures that England and Europe were experiencing in the 1530s 7. And I made two girdle belts as well – one “lighter” looking one with Gemstones on chain, and a thicker fiber one with a large tassel to go with the fur lined sleeves.

I then chose to make a French hood as opposed to the English version. With the sharp angles and having no hair exposed I feel it is much too harsh looking for my facial structure. And while extant paintings show the veil as always being black, I elected to use green in order to match the colors of the outfit.

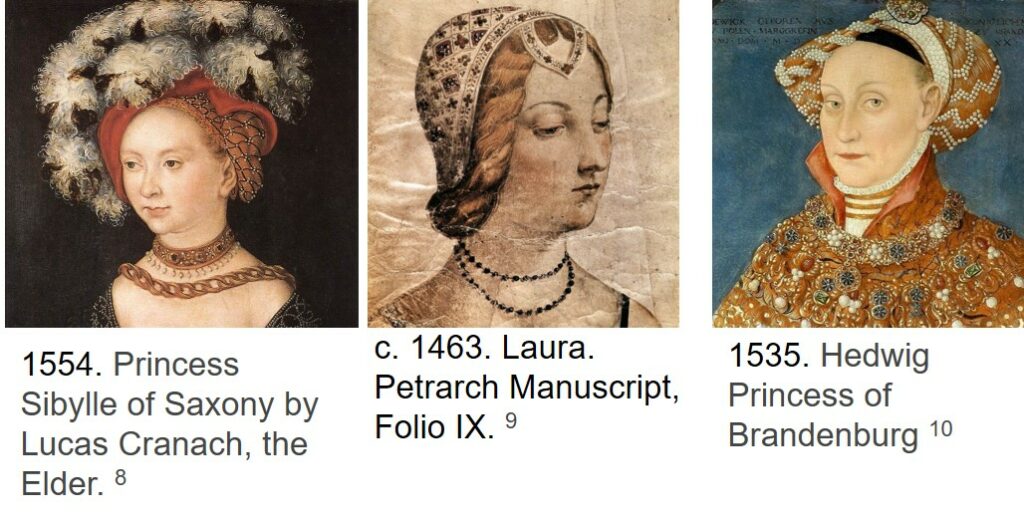

Under the hood I made a coif using a fabric that mimicked the look of English Blackwork. This I am in the process of beading (fingers crossed it will be completed in time, else I will wear a plain version instead). I have had some questions regarding the authenticity of extant beading of coifs. I have taken several classes on the subject of using beads in the Medieval, most recently at the University of Atlantia by Adair of Makyswell who has done extensive research on beaded items in period. I also located several portraits showing the coif or snood embellished with beads.

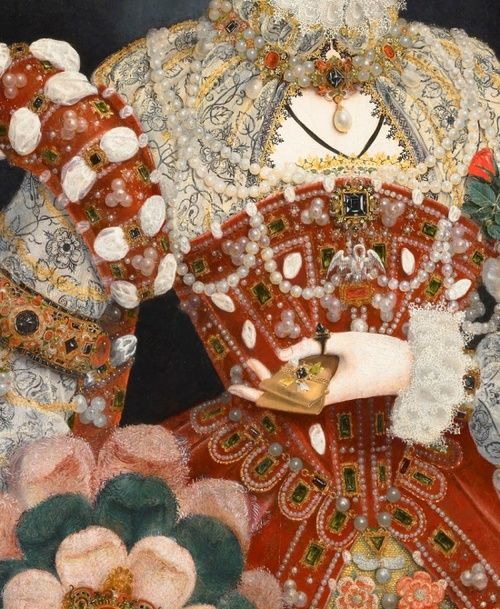

Another question I received was about my use of the large free-form natural, or ‘baroque’, style pearls I used on the neckline trim. Pearls have been used for millennia as decoration and even occasionally as medicine. All pearls until 1900 were natural not cultured. While portraiture most commonly show nobles and royalty showing off their pearls, which are most often round-ish or teardrop in shape. Because finding pearls was more a matter of chance, rather than mining as with gems, they were considered so precious as to only royalty and nobles were allowed to wear them11. Especially in the art of the Tudor and Elizabethan periods there is a large display of clothing and jewelry using pearls. As to the historic accuracy of the baroque style I present a picture of Elizabeth I wearing a gown heavily decorated with pearls in this style12.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1 – Portrait of Jane Seymour (1509?-1537). Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1540. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, Inventory Number 278

2 - Dressing A Tudor Lady from the Court of Henry VIII. The Tudor Travel Guide, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyEioB07qqk&t=2649s

3 – Leed, Drea (2021). History of the Elizabethan Corset, Elizabethan Costume. http://www.elizabethancostume.net/corsets/history.html

4 – Simplicity Pattern #2621 (2009). Simplicity Pattern Co. Inc., New York, NY.

5 – Simplicity Pattern #2589 (2009). Simplicity Pattern Co. Inc., New York, NY.

6 – Pastoureau, Michel (2001). The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric. Columbia University Press, Translated by Jody Gladding.

7 – Weather in History 1500 to 1599 AD. WeatherWeb dot net. https://premium.weatherweb.net/weather-in-history-1500-to-1599-ad/

8 – Princess Sibylle of Saxony and Duchess of Saxe-Luxemburg. Painted by Lucas Cranach, the Elder in 1554.

9 – Portrait of Laura. Petrarch: Canzoniere and Trionfi. c 1463, Manuscript (Plut. 141.1), Folio IX. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy.

10 – Hedwig Princess of Brandenburg at 1535, portrayed by Hans Krell (1490-1565)

11 – Hesselgrave, Barbara Lee (2020). Pearls – The Prestige Never Dulls. Manorial Counsel, Ltd., United Kingdom. https://www.manorialcounsellitd.com.uk

12 – ‘Pelican’ portrait, Queen Elizabeth I, c. 1575. Associated to Nicholas Hilliard. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, Ireland.