I’ll be posting my regular update tomorrow but here’s all of my documentation and some notes on what I did. As I’m still in the middle of finishing everything there may be some slight discrepancies between what’s written here and my final outcome.

Believe it or not this is the short version. Apologies.

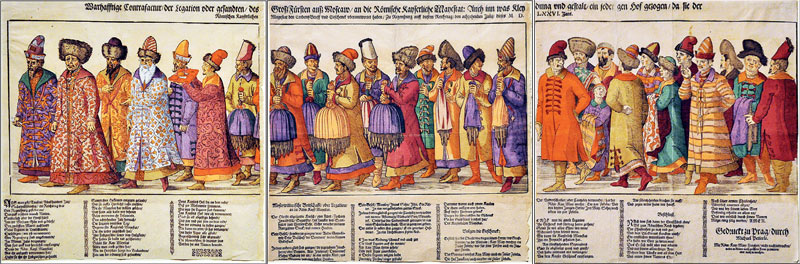

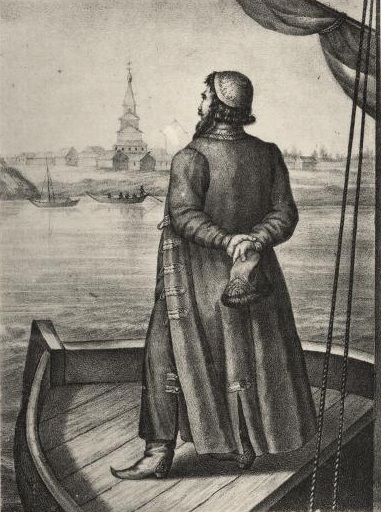

The clothing created is late-period Muscovite men’s clothing, specifically between 1500-1550CE. At this time the Golden Horde had officially ended its rule for over twenty years and Moscow had been ruled by a series of princes. The clothing is for a lower noble, a dvoryanin from a mildly wealthy family. While not as wealthy as the boyars, who were once princes in their own right, the dvoryans were an important counterbalance in the court.

Shirts:

- PDF Embroidery Books One and Two

- Traditional Russian Costume

“After the Tatar invasion, the opening of the collar, located in medieval Russia in the center of the chest, moved to the left side…and shirts which previously extended to the knee became shorter.” (Rezansky, 2019)

“The undershirt, or “shrachitsa”, is mentioned in many primary sources…Srachitsy were made out of bleached linen, thin wool, or even silk, and cut long and straight with triangular gores widening the hem and diamond-shaped gussets inserted under the arms.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

“An innovation in this period was the wearing of another upper rubakha besides the sorochka–koshulik, verkhnitsy or navershnika. With this, the sorochka was turned into proper underwear.” (la Rus, n.d.)

Both shirts made out of linen, patterned off of the ones in the grave finds. White undershirt with red embroidery to create a ‘fire border’ with the stereotypical off-centre neckline. Red and gold ‘bachelor’s shirt’ over, as seen in Ivan Kalita’s dream.

White undershirt fits a bit wrong; while it is not perfectly accurate it is comfortable and holds together. The red shirt is more accurate.

Pants:

“The pants, ‘porty’, were narrow around the legs and wide at the waist, with a gore inserted at the crotch. The top of the porty had no slit, and was secured around the waist with a drawstring (“gashnik”). Porty reached below the knees but above the ankles, and were always worn inserted into sapogi or onuchi.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

“By the end of the described period, porty were completely relegated to the role of underwear, and outdoors were worn topped with outer pants which could be made of fancy fabrics, leather, or even fur. The exact cut of these pants, however, is not known.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

White underlayer made out of linen, blue outer pants made out of a wool blend. Freehand pattern made based off of what I remember viking pants looking like. Extra drawstring case added to help with the line and fit. White porty ended up having a lot of fixing done on them–while I wanted them to sit close to my skin, they were a bit too close, and I busted the inner thigh seams a couple of times.

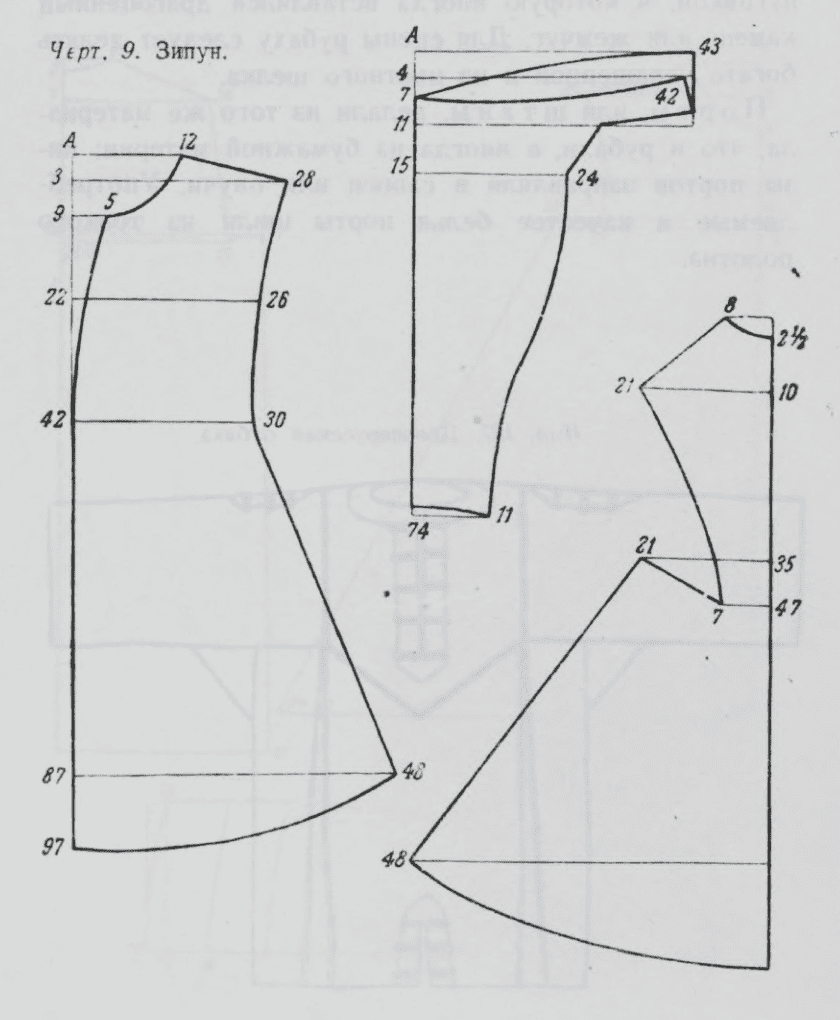

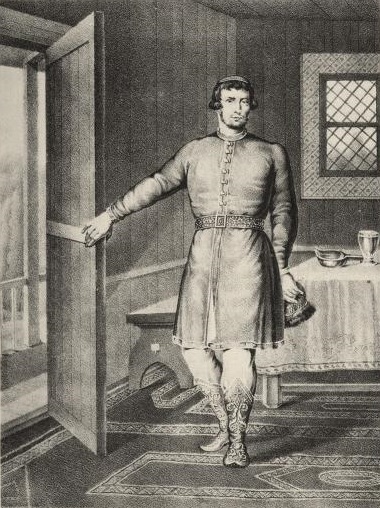

Zipun:

“A tight-fitting, almost skin-tight caftan, worn over a shirt. The sleeves were narrow and of normal length, closed using 4-8 buttons…Zipuny were usually knee-length, or sometimes shorter.” (Rezansky, 2019)

“During the period of the 13-17th cent. The zipun was a men’s indoor garment–a wrapped, rather short jacket, worn over the rubakha, but under the kaftan…One can think that the zipun functioned like the modern vest in men’s costume.” (la Rus, n.d.)

“ Referring to other authors, Rabinovich (p. 70) suggests that throughout this period men wore a “zipun” over their undershirts and under other layers of clothing. A zipun was a short, narrow jacket with narrow sleeves. Its construction, however, is not well documented in period sources. Like “kaftan,” the word “zipun” is Turkish and could have entered the Russian language either from Turkey or through the Tatar invaders.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

Gold poly-velvet with no added liner. Patterned off of the theatre patterns accessed in Rezansky’s site and then tailored. The sleeves were left larger than may be accurate, closer to a kaftan’s looser sleeves. This was based off of the patterns, as well as the fact that the kaftan would have slit sleeves and display the zipun sleeves.

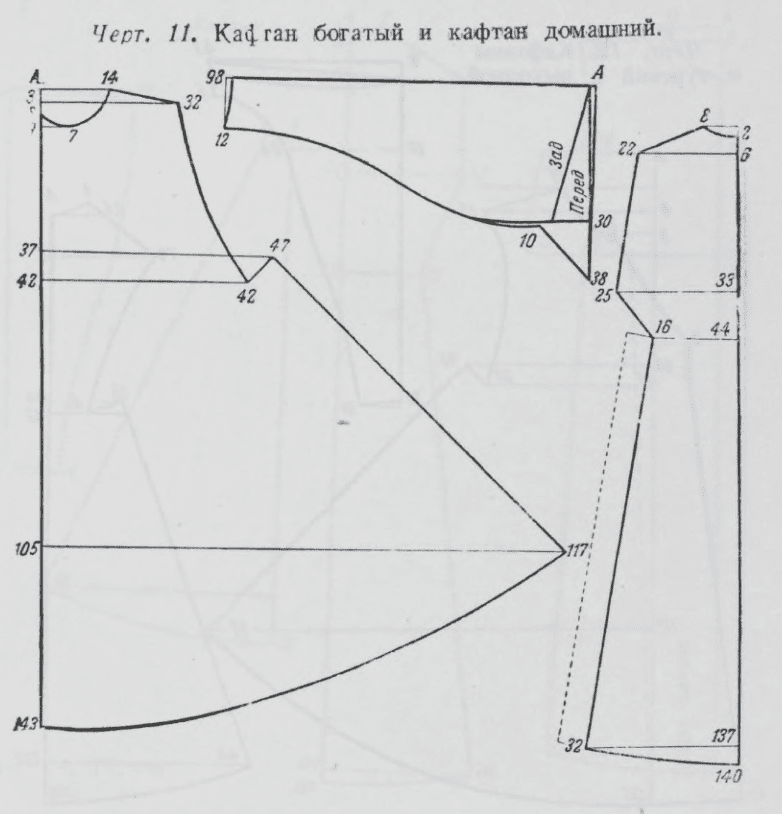

Kaftan

“Caftans were one of the most common forms of Russian clothing, and came in many varieties. Caftans were worn over a zipun, which it resembled in cut, but had longer sleeves; the excess sleeve was gathered above the hand.” (Rezansky, 2019)

“The word itself appeared in written sources in the XVth century, and by the XVIIth century came to refer to a variety of garments united by their basic design-a lined, buttoned coat, at least knee-length, where the right front opening covered the left front opening.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

“The use of sleeve slits varied along regional and cultural lines. For instance, Russians used both the open armpit and bicep versions, with the latter slowly increasing in popularity and flexible use from the 1620s onward as the former waned.” (syn Rostovskogo, 1995)

Outer shell made of Turkish upholstery fabric, lining made out of red wool blend. Based off of the zupan pattern as well as the kaftan patterns on Rezansky’s site. A center-cut was used instead of right-over-left overlapping due to the 1576 picture and Ivan Kalita’s Dream. There is a similar garment, an opashen, that is a slit-sleeve coat. Opashen are worn over other kaftans and are, according to some sources, favoured by older men.

Boots:

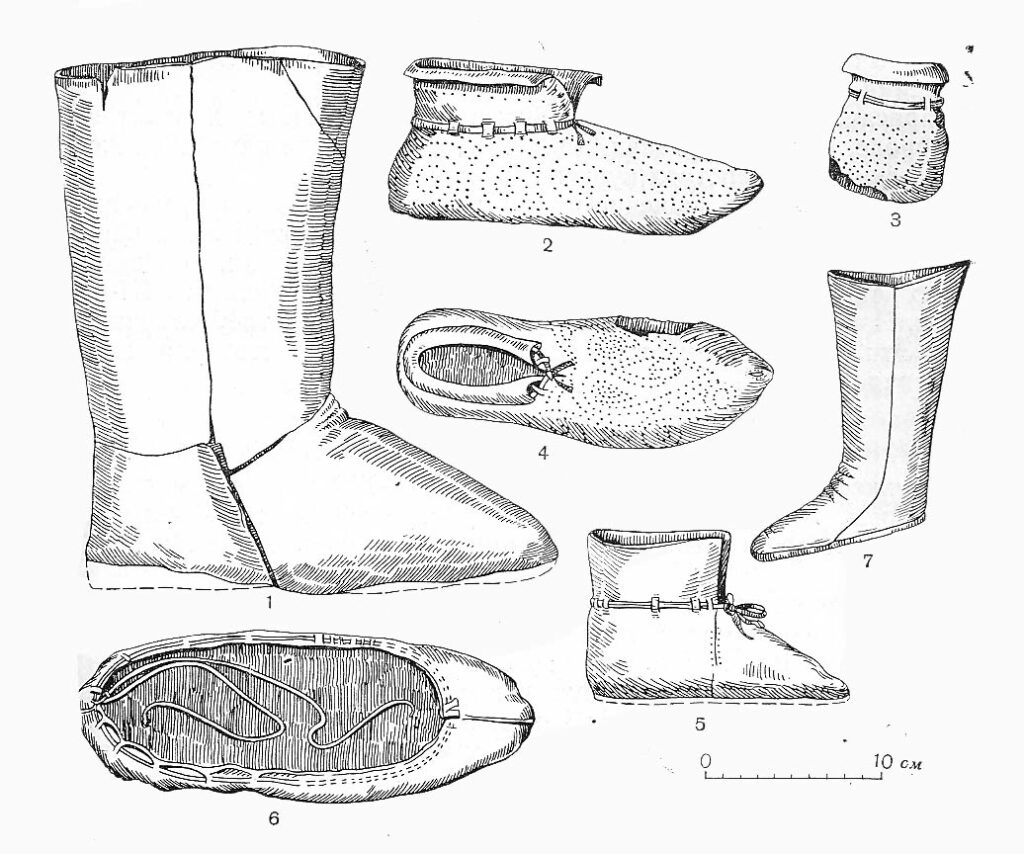

“Sapogi were mid-calf length boots, while ‘choboty’ and ‘chereviki’ were shorter.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

“The remnants of sapogi are found in the archeological digs of the cities much more often than any other footwear. Sapogi of this period had soft multi-layered leather soles, slightly pointed or round toes, and ended below the knee. The top edges were cut on a diagonal, so that a sapog was higher in the front than in the back. Sapogi were made on a wooden form without side differentiation, with seams on both sides of the leg.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

“Boots in the 15th-16th centuries were the most widespread form of footwear amongst the citizens of Novgorod. The majority had pointed, upturned toes.” (Rezansky, 2019)

Red cow leather boots. Patterned vaguely off of finds from Novgorod, as well as turn-shoes. First attempt at making boots as well as leatherworking.

Accessories:

“Young men would wear sashes at the waistline, tied rather tightly in order to emphasize the slimness of their figure. Those who were of a more mature age, and in particular those who were overweight, found it convenient to wear their sashes lower, highlighting the roundness of their bellies.” (Rezansky, 2019)

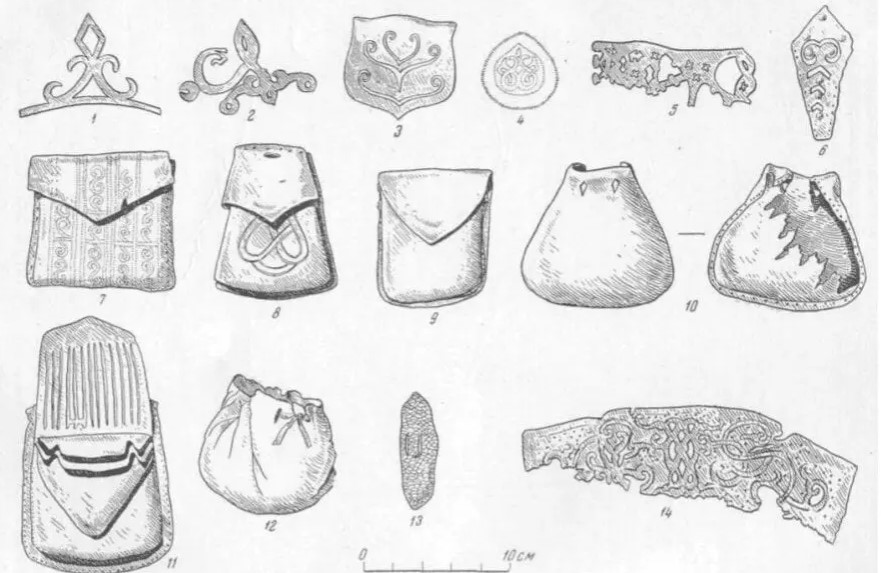

“Belts and sashes were made from leather, silk, brocade and velvet, decorated with embroidery, silk, gold, pearls, precious stones, forged metallic plaques, gold braid, etc. Frequently they were decorated with an array of pendants and decorations, as wells a money purse (kalita), a small bag like a wallet, used into the 17th century…From a belt or sash they would wear a knife, a kinjal, or sometimes a knife and spoon.” (Rezansky, 2019).

“Underneath this outer headwear they would wear a taf’ja…a small hat which covered the top of the head. These hats were also worn continually at home. A dressy taf’ja was made of silk of various colors, gold, pearls, and precious stones.” (Rezansky, 2019)

“Another form of hat was the kolpak, which was somewhat pointed with satin, broadcloth, velvet or gold fabric, and which instead of fur trim had a raised brim in the form of a lapel.” (Rezansky, 2019).

“In the XII-XVIIth centuries, especially towards the end of this period, the “kolpak” was the most popular form of men’s headwear. A kolpak was a tall conical cap turned out at the bottom to form a sort of a cuff, which could have one or two holes for attaching decorations: buttons, clips tassels, or fur trimmings. Kolpaki were either knitted or sewn of any kind of fabric, depending on the owner’s income.” (Vladimirova doch’, n.d.)

“A second style was used for round pouches. They were made from a single piece of leather, pulled together at the top with a drawstring. These works were typically very plain in outer appearance, without any decoration. These date from the 12th-15th centuries.” (Rezansky, 2020)

Red cow leather money bag.

Kolpak (outer hat): red wool blend lined with grey rabbit’s fur. Four-piece football half pattern.

Taf’ja (skullcap): white linen with cotton embroidery.

Sash is a green linen-cotton blend.

Works Cited

Колпак (головной убор). (2009, May 22). Wikipedia.org; Фонд Викимедиа. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Колпак_(головной_убор)

la Rus, S. (n.d.). Rabinovich 1986 Appendix Translation. Http://Www.sofyalarus.info/Russia/Garb/Rabinovich86app.html; Retrieved January 22, 2021, from http://www.sofyalarus.info/Russia/Garb/rabinovich86app.html

Orli, R. (2001, May 10). Polish XVII C. Costume. Web.archive.org. https://web.archive.org/web/20150510140149/http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse/PoleCostume.htm

Rezansky, I. M. (2019, November 10). Russian Historical Costume for the Stage, Parts II and III. Ivan Rezansky’s SCA Adventures. https://rezansky.com/russian-historical-costume-for-the-stage-parts-ii-and-iii/

Rezansky, I. M. (2020, October 27). Leatherworking and Shoemaking in Novgorod the Great | Ivan Rezansky’s SCA Adventures. Ivan Rezansky’s SCA Adventures. https://rezansky.com/leatherworking-and-shoemaking-in-novgorod-the-great/

Shoes. (2009, November 19). Users.stlcc.edu. https://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/Slavic/shoe.html

syn Rostovskogo, M. S. (1995). The Russian Coat and Variations for the Practical Clotheshorse. Mordak Coat. http://sofyalarus.info/russia/Mordak/mordakcoat.pdf

Тафья. (2010, April 24). Wikipedia.org; Фонд Викимедиа. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Тафья

Vladimirova doch’, L. (n.d.). Russian Dress in IX-XVII Centuries (with Focus on Women’s Dress) (S. Evodia, Ed.). SCA Russian. Retrieved January 25, 2021, from http://www.scarussian.com/costume.html

Figures

Fig. 1

The Praying Novgorodians (Novgorod). (1467). Museum of History, Architecture and Art. https://www.icon-art.info/masterpiece.php?lng=en&mst_id=573

Fig. 2

Grand Sakkos of Metropolitan Photios (Moscow). (1415) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vasiliy_and_Sophia_(sakkos_of_Photius).jpg

Fig. 3

Котлякова, T. H. (1963). МУЖСКИЕ РУБАХИ КОНЦА XVI- НАЧАЛА XVII В. ИЗ ПОГРЕБЕНИЙ ЦАРЯ ФЕДОРА ИВАНОВИЧА, ЦАРЕВИЧА: ИВАНА ИВАНОВИЧА И КНЯЗЯ М. В. СКОПИНА-ШУЙСКОГО В АРХАНГЕЛЬСКОМ СОБОРЕ МОСКОВСКОГО КРЕМЛЯ. ТОЖЕ ГОРОД. http://www.tgorod.ru/russia/rubahtsar_files/rubaha.htm

Fig. 4

Ivan Kalita’s Dream (St. Peter with his Life) (Moscow). (1580). Assumption Cathedral, Kremlin. https://runivers.ru/gal/gallery-all.php?SECTION_ID=7590&ELEMENT_ID=475726

Fig. 5

Buffcoat “caftan” or zupan. (n.d.). In 17th C. Muscovite/Russian Costume. http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse/Costume/MuscoviteGear.htm

Fig. 6

Rezansky, I. M. (2019, November 10). Russian Historical Costume for the Stage, Parts II and III. Ivan Rezansky’s SCA Adventures. https://rezansky.com/russian-historical-costume-for-the-stage-parts-ii-and-iii/

Fig. 7

Rezansky, I. M. (2019, November 10). Russian Historical Costume for the Stage, Parts II and III. Ivan Rezansky’s SCA Adventures. https://rezansky.com/russian-historical-costume-for-the-stage-parts-ii-and-iii/

Fig. 8

Russian Embassy to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, Русское посольство к императору Священной Римской империи Максимилиану II. (1576). In Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Russian_embassy_(1576,_engraving)_page_1-3.jpg

Fig. 9

Artsikhovskii. (1969). Shoes and Boots from Novgorod, Russia. In Shoes. https://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/Slavic/shoe.html

Fig. 10

Boot from Novgorod. (n.d.). In Novgorod Museum. https://novgorodmuseum.ru/images/wssgallery/6399efe5b79598baa995233f8a623319.jpg

Fig. 11

Rezansky, I. M. (2020, October 27). Leatherworking and Shoemaking in Novgorod the Great | Ivan Rezansky’s SCA Adventures. Ivan Rezansky’s SCA Adventures. https://rezansky.com/leatherworking-and-shoemaking-in-novgorod-the-great/

Fig. 12

Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.-a). Russian clothing in the XIV to XVII centuries, single-row taffia and hat. In Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:01_011_Book_illustrations_of_Historical_description_of_the_clothes_and_weapons_of_Russian_troops.jpg

Fig. 13

Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Russian clothing in the XIV to XVII centuries: Zipun, tafya and hat. In Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:01_017_Book_illustrations_of_Historical_description_of_the_clothes_and_weapons_of_Russian_troops.jpg